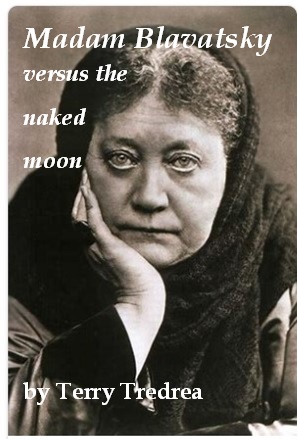

1. Madam Helena Blavatsky, 1890.

At the signal, Elspeth smothers all candles, except this one that she brings through the darkness like an offering of gold to Helena. Around the circle of acolytes, breathing hushes, and the silk curtains shiver for a moment. Helena takes the candle and holds it up, relishing their attention in it, the pleasure of playing with them for a while. She loves this allure of candle-flame in the blackness she has created. The charms of radiance. She lifts her arm: “Blessings be upon your spirits,’ she says, ‘with grace from Holy Ones,’ gesturing over them with a chinking of bracelets.

‘And upon you, Beloved,’ they murmur, in a soft, apologetic hum.

Into the rustling gloom Helena thrusts the candle, searching the faces of her dear followers, prowling among them as always for her successor. She studies her alert young women with their short hair and open faces, her soft young men of unfashionable locks, gaunt with the strain of holding in semen. What a fine flock she has collected. Though they scatter at her bidding, and none so far has stood and said, ‘Enough Helena. Listen to us now.’ Yet before she dies – and at 63 her death feels close – she must choose one person to be her voice when her own voice is dust. Surely her divine Master can oblige her with one person. Surely her faith deserves reply. But her Master, whose answer is overdue, is like a demented uncle on whom one depends for money.

‘So let us reach out…’ she says, ‘beyond grave.’ Somewhere a small bell tings, and they sit forward like balloonists ready for lift-off. The candle dazzles like a slit of light slicing the dark. The air is humid with incense, the sweet, musk smell of the candle, and what she has come to recognise as her own gas. It seeps carelessly from her, this acrid betrayal of her body. But what can the doctors do? The silence of the room whistles in her ears. ‘Are you here, Master?’ she asks, and hears a knocking to begin the late afternoon show. ‘Reveal your message for us.’ But she must wait to catch her breath. Clearly the damn doctor is losing the battle.

At last in the expectant hiss, an empty chair begins its shuddering and clunking. There is a ripple of sighing amazement, though Helena has summoned spirits often enough. She speaks into the silence: ‘Will you soon reveal your Chosen One, Master?’ A juicy ten seconds passes before the yes comes in a tiny tap-tap. Could this really be Him, scratching away in the ethers, rewarding her devotion? She dares an almost deep breath, and winces. The air in this sealed room is thick and musty with her tobacco smell. She flaps her wide skirt, relishing the cool in her armpits.

The afternoon is a success, with one levitation and the unseen bell tinkling. Some kind of spirit appears like a shimmer of incense smoke. It hovers above them, skittish and crazed before swooping off. How exciting these “appearances” are for the acolytes – like a Brahms recital. And the spirits are more than usually talkative, rapping and pecking away under the table. Helena feels a tiny confidence that perhaps her Master will at last reveal His Chosen One, that the signs favour His last-minute intervention.

Finally, Elspeth ignites a sprinkle of small candles. ‘Aghhh,’ Helena sighs, settling back. “So… what is news?’ and gazes around the circle, piercing them with her stare. Such soft creatures, she thinks. And who among them is worthy of my life’s Great Work? Who will keep it alive into coming, perfect 20th Century? Elspeth maybe? Ashton? Which one has that fire of soul, that flash of divinity to champion my unfinished masterwork? My sacred legacy? She watches their shy silence, and waits, wheezing. The candles quiver.

‘All right,’ she says. ‘Let us pray,’ and twelve heads drop.

There they sit, her twelve disciples, devout as she can get them, but none is what you’d call a John the Baptist. Full of zeal, of course, but somehow…can she say flaccid? ‘Oh, Christ,’ she hisses, rocking forward and frowning at the ceiling. ‘Give me strength.’

Elspeth perhaps?

Earlier, Elspeth had come whispering at Helena’s door, “Beloved,” fine as the nibbling of a mouse. “Your prayer group is waiting. We must hurry.”

Must?! Anger had erupted up Helena’s spine.

“Madam? The prayer group?”

Dear God, she had prayed, why me? Of all the rebellious girls of Russian nobility, surely I am the last one God should choose. Me – who once plunged her foot into boiling water to avoid the choking conventions of a “grand” ball; me who fought all her grandmother’s “musts” with a warrior’s proud resolve. And yet here I am, expected to obey God’s will and serve His “musts”. Sentenced, it seems, to wade the mud of this world alone. Yes it is mud, and God has rained on me so long that I no longer care to open an umbrella. Dieu. She’d thrust ringed fingers through her crinkled hair: maybe it’s true – whom God loves He drowns in torments.

Another scratch at the door. “Beloved?”

“I am meditating!”

She’d rattled out a cough, then wet her tongue and run it along the cigarette she’d built. It burst to life and fizzed under her hungry sigh. Ah, dearest cigarettes, since that first rapture in Cairo thirty years ago – or maybe thirty-five? Was she ever so young? She had fallen in love with cigarettes but swooned for hashish. She sank back into her chair, smoothing out the expanse of her dress, and admired the glow of bracelets along her arms, her clusters of rings lustring each finger. Clearly she has learnt something from Old Russian Church, growing up among all its glitter – like how to enchant a crowd with a few candles and bells. How to awe her serfs with stories of goblins and water spirits. What glee to see their faces gape in belief, smile with hope. Yes the world is still full of willing serfs, even here in modern London. And why not?

Elspeth shuffled at the door. “Two minutes!” Helena shouted. “Bugger off!” She can’t help herself – it’s the way they all slink about house.

She’d lifted her legs, rolling back and forth to joggle herself to the front of the chair, and in a bluster of panting and wheezing heaved herself up. She stood a moment, to check herself in the mirror – ah, there she is, the famed author of The Secret Doctrine and The Voice of the Silence – a woman of influence indeed – yet squeaking for breath, her head spinning and skin swollen like tripe. Was this God’s little joke on her? Still, there stood the woman she has loved all her life, loved her blaze of cobalt eyes and her electric red hair. As the Irish poet said, “Madam, you have more human nature than any of us”. Such a sweet young man. But merely human nature? Not also touched with the divine?

She had waded out into the receiving room, trailing a line of smoke, with Elspeth hurrying ahead to open doors. And sometimes Helena lusts for her riding whip, for one quick crack to scatter them all like sheep before a horse. To see if any will turn and fight. “Stop!” she’d said.

“Yes?” said Elspeth.

“Don’t you feel it?” Helena pointed at the ceiling and nodded. ‘Huh?’

Elspeth squinted, flushed and blinking up into the empty air.

“Spooks,” said Helena, skewering Elspeth with her glare. “They are uneasy. Yes?”

Elspeth’s eyes skated the room, flew into high corners: “Yes, I think so.”

Oh, Christ, thought Helena, let it go. “Quickly!” she said, and they had bustled into the vestry.

Probably not Elspeth. But who else?

The acolytes have begun to shuffle and fidget from waiting too long for Helena’s prayer. She inhales, and delivers the announcement she has nursed to herself all day, has savoured in her mouth like a luscious fruit: ‘Mrs Annie Besant…’ she declares, and eyes them. The name has the startling impact of smelling salts. ‘Eminent Mrs Besant herself may perhaps visit me this evening.’

Ashton unclogs his throat. ‘To give a lecture, Madam Blavatsky?’ He stares, intense with fatigue. ‘Something educational?’

Helena feels her heart rally at the delicious possibility, ‘I…’ The bitter impossibility. She has read Annie Besant’s stirring articles, and saw her once speak to a crowd in a battle cry of magnetic authority: a small, erect woman rousing a hall of working men to shouts of outrage. Her calls rang like an ironmonger’s hammer and the crowd yelled Yes! She had shouted as if all the world listened, and maybe it did, inflamed by this warrior of a woman. Helena frowns: ‘Perhaps just a visit,’ and pouts against further questions.

Now they sit forward, eager for other miracles to report back to the Society. ‘Mrs Besant,’ she says, relishing how the name brushes her lips, ‘she is…’ but tears, which she has not spilt since she was fourteen, and then only in anger, are rising foolishly behind her eyes. ‘Masters,’ she clears her throat. ‘Masters are very excited at Mrs Besant’s… visit,’ as surely they must be. Surely.

‘What can we do, Madam?’ asks Mabel.

Keep out of her bloody way, thinks Helena. Instead she says, ‘We must impress her with our seriousness, beloveds. Because she is, as everyone in civilised world knows, a serious person. And what she may write and speak about us can sway public opinion more than one speech by, say, Mr Shaw, or even one play by Mr Wilde.’ Helena spreads her arms with a clapping of jewellery, ‘…God has sent her to us.’ They smile and glance shyly around. ‘Let us pray.’

Twelve heads fall. And again she must wait to catch her scorching breath. No doubt her doctor is losing this fight:

“Your drops of tincture, Erasmus,” she’d plainly told him, “burn my mouth and make me itch. You enjoy torturing me.”

“Science tells us, Madam B, that you must let every experiment run its course.”

“Am I one of your laboratory rats? And what if experiment is success but rat dies? Will you feel satisfied, Dr Wedgewood? Will science not prove itself once more helpless before God’s will?”

He merely smiled deep in his beard and stared down into her saggy, blazing eyes, seeing only specks on the retina and missing the immensity of her soul.

These days, she feels as if she is sinking in some icy, black sea. This premonition of herself haunts her – as a doomed ship plunging into the frozen night, still glowing with ballroom lights, syrupy with violins and mirth, yet pitching into a salty, ink-black oblivion of fish. And all the smart and beautiful passengers of her long life spilling and drowning. Forever gone. She shivers. No-one of substance seems left alive.

‘Yes, we pray,’ she says. ‘Oh beloved Masters, hear us…’ But Helena can imagine a year from now, maybe less, her Theosophical Society ploughing on without her at its helm, still proclaiming the Brotherhood of Saints and the Evolution of Humanity, but now under the presidency of that hog’s arse, Godfrey Horlock. Ah, she needs a pistol. Just one bullet would rid her precious Society of that slithering worm, who by oily insinuation has slid his way into the Presidency. “Dearest Madam,” he smarms, “you hold humanity’s destiny in your hands,” meanwhile plotting with that limp slug Spencer Beasley to cut the Society off from her own Esoteric Group. Vile impudence of it! Helena clenches her jaw. “You, Mr Beasley,” she had taken pleasure in announcing, “have been observed flirting with Mrs Farbrother. You are both expelled. Now kindly take your odious presence elsewhere!” Sheer orgasm, watching him skulk. Which he did – along with a spineless third of her Society. Good riddance. No, she must not die now. Please God.

‘Beloved Masters, heed us!’ and she revs her raw, smoker’s throat. ‘Awaken within Mrs Besant the radiance of your presence. Emblaze her, till mists of ignorance burn away. Then lift her into clarity of your Himalayan vision, that she may join us.’ She imagines her prayer ringing in heavenly corridors, divine heads turning, perhaps slightly annoyed. Not bad. ‘Amen.’

Still they wait, these followers of hers, these fine and fragile curiosities, expecting miracles, or at least a candle to dance in the air before them. Dieu, what a circus it has become, juggling her books, performing her lectures, dancing her divine dance before each ravenous crowd. A dance of love, for the most part, and so it must go on, forever; somehow it must, at Master’s service. Helena, perform for us. She sighs. All this for her… her Master’s timeless Wisdom. Wherever He is.

An hour later, alone in the drawing room with just the scratching of the clock and a stupid bird wittering by the window, Helena itches all over and her breath comes in little gulps. She is sore and cold and aches for rescue. But Mrs Besant, of course, is a woman of the world, with great matters of social justice to pursue. What interest could she have in Helena’s fancies? Like calling a wild eagle down to perch on your arm. Absurd. Helena scratches and kicks with frustration. A clay Buddha cracks to the floor. ‘Oh fucking hell!’ she cries.

‘Madam B,’ Elspeth murmurs from behind the hall door.

‘What merde now, Elspeth? What?’

‘Mrs Besant, Madam.’

‘What of her, you idiot?’

‘She is here.’

A shiver almost shakes Helena from her chair. Gas escapes. She jerks herself upright; she feels like a diver edging towards a cliff, afraid of the depth of water below. She sucks for breath, feeling hot and cold. ‘Christ, let her in, girl. Bring us tea.’