Journeywoman – The Story of an Asian Prostitute

When I was five years old, my mother became pregnant to a crow. A very common crow. Yet my brother was born looking less like a crow than a small, crumpled man, red with outrage, screaming curses at us for disturbing his sleep…

Each in her corner, we couch in shadow wrapped in silk. The nature of this place is not obvious – the eye comes by faith to omens of shade. Customers grow from the night, slide their money across Pheu Wang’s desk, choose with care. We uncoil along the benches, legs apart, writhing with mock desire.

‘Move, you slugs!’ Pheu yells. ‘Do you think this is a temple?! Shall I put out some joss-sticks?!’ His voice is a raw grumble.

A large Arab lounges in the foyer. His dark eyes shine through a halo of smoke. One finger rises towards me. ‘That one.’ I follow him into a bedroom, lie down like a fish awaiting to be gutted.

At 2.00am the light smacks on, and someone is screaming and jabbing me with a stick. ‘Up, you bastard!’ I hunch into the wall, blinking in the sharp light, but a boot digs me out. Four of them fill the tiny room, green uniforms, staves. They crowd us to a wall. ‘Clothes off!’

We drop our tunics on the cement, stand before the armed and booted women, soft as virgins. These ‘surprises’ are no surprise anymore.

When a door has once been broken open, it is difficult to keep it shut.

Back to Top

Our Privacy Your People

‘Mine is an old Australian family; the family that moved in next door is nevertheless much older.’ Thus the Reverend Warwick Feather, lapsed-Christian, encounters his indigenous neighbours. He ignores them.

But when the neighbours’ extended family announces a sacred site beneath Feather’s church, then events turn complex and fiery: “Your church is a blow-in, Reverend. Jesus just rentin’ upstairs flat!” So the indigenous people lay claim to the site, and begin tunnelling the church away.

Feather’s deacon, Garth Pike, hot from Theology College, sides with the ancient people: “We have been chosen to help these poor people, Warwick. They are our mission! What’s a church, here or there?”

And the Bishop, he whose eyes slide away into corners, has his own plans for making publicity from the event. As has the government of the day. Meanwhile the church, despite the best of traditions, is sinking. Feather’s wife, Penni, a woman “whose family come in six-foot lengths,” demands he move the squatters out. “Penni, the meek shall inherit the earth,” pleads Feather. “Warwick, some of them can’t wait.”

The police become involved; Feather becomes involved (“Your flock got any black sheep, Rev’rend?”). He is drawn to the vitality and sincerity of his squatters, despite the threat to his beliefs, becoming cornered and alien in his own church.

The police move in, and Feather must take sides, or fall into the sacred hole dug between two cultures, two laws, two peoples. Deemed ‘politically incorrect’, this novel goes to the heart of intolerance seen through the eyes of a well-meaning European incapable of rising to the paradox of a white society in a black land.

Back to Top

Grieving the Fatherland

“Exile is the defining experience of the Twentieth Century.” – George Steiner.

“Fuck off back where y’ come from!” This is the greeting Nguyen Tran Manh hears daily from the natives of his adopted Western country, having fled his homeland in fear for his life, exiled from his family perhaps forever.

A teacher in his homeland, Manh runs two jobs – one in a factory among dangerous machinery, the other as a gardener for a wealthy, neurotic woman (“If these people are not royalty, why are they in palaces?”). Letters arrive from his family, detailing their persecution (“I carry these letters against my chest, like a disease.”). He determines to gather money and points for the Points Test, in order to bring his family out. But his wealthy employer is so bizarre to him, his factory foreman so given to fits of “madness”, that every moment he expects to lose both jobs and all chance of rescuing his family from the hateful Regime.

Manh grieves for his lost family, yet recalls disturbing memories of family tensions and the coldness of his father. He is torn between longing and anger, love for a family who punished him with guilt. (“What words could reach his bitter ears? Words from his eldest son, once beloved, who ran away?”). He broods on his homeland: how history has split it, politically and spiritually, and fears it will destroy itself as internal forces grind it down.

He becomes involved with two very different people. One is Christy, a strange young woman in the next flat. “I think she is a prostitute A decent woman, my mother would say, does not advertise herself. The girl next door seems to live by no rules of honour or dignity or restraint.” The other is Hung, a fellow countryman obsessed with revenge, with returning to fight and free his country. While Hung urges Manh to answer the call to duty, and free his family, Christy slowly draws him into the life of this “decadent” new land, to become a little of both cultures, until he cannot recognise who he is and where his future lies. Meanwhile his father is taken away again to re-education camp, his family thrown onto the street (“living like mice on scraps”).

So when he finally has the chance to rescue his parents, he must decide between escape and armed resistance, between duty and survival, between love and hate for his father, between East and West; or perhaps find some strange place halfway between the two.

“[Of my homeland] I have to remember everything, / keep track of every blade of grass” – Pablo Neruda.

Back to Top

Beach House

When a family of five very different, grown siblings return to their family home on the coast for their mother’s funeral, the challenge of consoling their devastated father arouses all the tensions between them. Their father muses on his loss: “Too much of me is in her for only one of us to die.” “People expect courage; but what can you hang courage on when you are dangling?” When the five siblings leave him for an afternoon, he goes missing at sea, and the children go in search in a small boat: “…so that rubbing together we are like dry sticks ready to ignite.”

Jo, the eldest, is a doctor, “her eyes narrowed, flinching against any leakage of tears.” Sidha, a brother who lives in the metaphysical now, often smiles, “though you cannot tell,” thinks Lee, “if he is indeed in touch with some basic wisdom, or just feeble-minded.” As they begin to argue about their father’s possible death, Lee the narrator decides, “Maybe we should put up a sign – Death is Forbidden Here. Yet my mother has already broken the rules, dragging death like a stinking carcass into the loungeroom, fouling the air.” Lee is haunted by glimpses of her dead mother.

Clarial, a minor television evangelist, sees “God’s will in everything”. When their father is found and in need of medical help, Clarial says, “He needs the assurance of faith, Jo. Comforting thoughts.” “Dad’s not a cretin, Clare. He can recognise basic facts when he sees them. He needs proper care in hospital.” “Hospitals are just body shops, Jo. What our father needs is a cool bath and care. Just to feel our love.”

But Juliard, the youngest, a libertine anarchist, has another view of events: “Beneath the bullshit, we’re all beasts”. Rough words foam like strange growths on his beautiful lips. “Juliard, in the flesh,” says Sidha. “My favourite way to be,” says Juliard. “I think Juliard is wise the way insects are wise,” thinks Lee.

As a storm gathers, the siblings circle each other, at odds about how to deal with their ill father. Each explores in retrospect their relationship with their parents, and with each other as they battle for control of the family. Even their father, in mild coma, reviews the mistakes of his life.

Finally, as they realise that “this lovely house rests on a brittle decay of walls,” they must cope with the breaking open of all inhibition and face the challenge of the storm and the presence of each other in their lives.

Back to Top

Floating

Floating is about three people in different forms of exile, who begin thousands of kilometres apart, and come together with a devastating impact on each other.

An Iranian Baha’i escapes her country when her husband is murdered, desperate to smuggle her son to safety any way she can, regardless of the dangers. Yet, “is it so very wise to flee,” she asks herself. “…to abandon everything that defines us, and fly like specks of dust west across the desert? …to be scattered by the winds of politics forever around the planet?” There is no choice for Salinah Mahrami but to engage a people smuggler and expose herself and son Afif to the ocean journey to Australia. Her only hope of resettlement becomes her Australian lawyer in whom she has no faith.

Meanwhile, this same man, Liam, divorced and in exile from his family and city is trying to revive his life in Sydney when he receives an anonymous photograph of a young Anglo-Asian woman. He suspects she may be his child, “like a daughter I did not have.” Haunted by her image and the compulsion to find her, be begins to lose hold on his fragile relationships with his real daughters and his lover.

Thirdly, a young Australian-born Vietnamese woman is manipulated by her parents into making a pilgrimage to the “homeland” she would rather ignore. “Until you go, San-Lin, you don’t know who you are,” says her father. “‘Now is Tet,” says her mother. “In your father’s village, they must take you in…” But San-Lin thinks she is Australian, “I belong nowhere if not here.” Yet once there, she discovers a passion for her cultural origins, and finally the secret behind her parents’ agitation.

Their individual quests gradually converge, while their search for home takes them further away from where they thought they belonged.

Back to Top

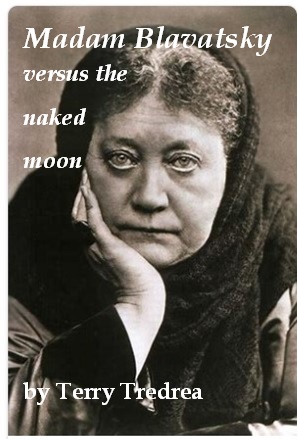

Madam Blavatsky Versus the Naked Moon

Madam Helena Blavatsky, a runaway Russian aristocrat, charmed Victorian society with her séances and books that claimed to be “transmitted” from holy ones in the Himalayas. The rich and elite flocked to her Theosophical Society, infatuated with the promise of everlasting life and a coming messiah. W.B. Yeats called her, “more human than the rest of us”. The young and idealistic built an esoteric community around her. George Bernard Shaw called her, “one of the finest imposters of her time”. Oscar Wilde called her, “a grumpy old man”, a hard-cursing, bellicose, chain-smoking tyrant.

Shaw had reason to resent her. His dear friend Annie Besant was the leading emancipist, educator and workers’ rights advocate of the times. She was an indomitable fighter for human rights, with a pragmatic skill for social reform. Then she joined Blavatsky.

This is the story of that impossible partnership. A period of 50 years of turbulent social revolution is compressed into one incendiary year. Told through the voices of Blavatsky, Besant, Shaw and Wilde, it is an historical fiction, half of which is factually correct, and all of which is true.

Back to Top